Could higher interest rates help the economy?

May 4, 2012 Leave a comment

We live in an age when central bankers grace magazine covers like pop stars. But what if they don’t actually know what they are doing? In the United States, at least, quantitative easing and low short-term interest rates may have done as much harm as good.

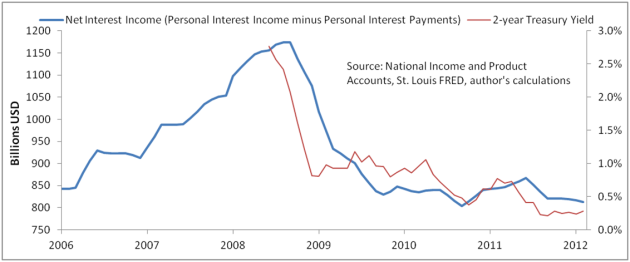

Thanks to the collapse in borrowing costs, Americans now earn $361 billion less in net interest income than they did in the summer of 2008. This is equivalent to 2.4% of GDP. The beneficiaries are those taking on more debt. Since the private sector and municipalities are still retrenching, that means the federal government. Low rates are thus transferring income from the people to the state—fiscal austerity by other means.

Generally, lower interest rates make borrowing, spending, and investing so attractive that the decline in interest income is more than offset by new earnings elsewhere. In a balance sheet recession, however, the private sector is unwilling or unable to take on more debt despite negative real interest rates. American households are rightly focused on recovering the $8 trillion of personal net worth that has vanished since the middle of 2007. Unsurprisingly, businesses would rather hoard trillions of dollars of cash than invest; there is no point in expanding capacity when there are no customers. Thus, despite the Fed’s aggressive attempt to revive animal spirits, Americans are repaying debt instead of taking on more. The stock of nonfinancial private debt is still smaller than it was in 2008.

Could monetary expansion have stimulated the economy through some other channel? Textbooks say that the Fed’s policies made the dollar relatively less attractive to foreign savers, boosting the economy by improving the terms of trade at others’ expense. Guido Mantega, the Brazilian Finance Minister, notoriously argued that the United States was deliberately devaluing the dollar in an act of “currency war.” Yet the only academic attempt to define and quantify the effects of the Fed’s policies—admittedly published by the New York Federal Reserve—never mentions the exchange rate.[1] The Bank of England put out a working paper on the effects of its QE program and its conclusion was that “one interpretation of sterling’s relative stability would be that QE has not fundamentally changed market participants’ views of its relative prospects.”[2] And if the U.S. was in a race to the bottom, it lost: the broad trade-weighted dollar is more expensive now than it was in mid-2008.

The Fed might have been an unwitting accomplice to the anemic recovery. That would be bad, but the coming fiscal contraction will be far worse. Unless the law is changed, severe tax hikes and spending cuts will hit at the start of 2013. A compromise may not be reached before it is too late. The Fed could help by raising rates. This would force the government to spend more money on debt service—fiscal stimulus by the back door that would buy time for further private deleveraging. Ideal? Hardly. But it just might be the best option available.

[1] “Large-Scale Asset Purchases by the Federal Reserve: Did They Work?” by Gagnon, Raskin, Remache, and Sack, FRBNY Economic Policy Review, May 2011

[2] “The Financial Market Impact of Quantitative Easing” by Joyce, Lasaosa, Stevens, and Tong, Bank of England Working Paper No. 393, July 2010, revised August 2010, p. 28